Notes dated 2/4/22: We sit on the sandy banks of a country park from my childhood today, and I think about my dad.

I contemplate how the local 192 bus journey (my hometown bus) continues along the snaking stretch of the A6 road every day, as it has my whole life. How people weave in and out of shops, each other's lives, dodging human traffic to get home.

I reflect on how this continues without my dad, as it has for the years since he passed away.

Today, at this country park, my two daughters build a bridge from moss-coated tree branches and large pebbles they have collected with two hands from the water's edge just beyond the sandy banks where I sit and watch them.

We sit on coats amongst the stubby nettles and dirty sand, soaking up the intermittent sunshine that casts shadows across the land and water.

I used to come here to skip stones on the water's surface with my dad, and now, here I am, with my own two, doing the same.

I come here to try and grasp the ghostly hand of my dad.

I’m chasing him down the streets where we'd take our dusk walks (my tiny, cool hand in his big, warm hand). We'd walk to Braithwaites, the corner shop, to buy crisps and pop (for me) and too much beer (for him).

There's a cloud of a memory, like the residual scent of perfume as someone walks by, and it's as though he's just passed through me. His presence breathes and echoes along this well-known street.

I can hear him clearing his throat and feel the roughness of his palm against my own. I feel his essence. I'm drawn back to this place I know so well from when I was half the height I am now, and when I was full of love for everyone and everything.

The sun and shadows, those fast-moving clouds, symbolised the days I knew so well.

What am I expecting?

What am I expecting to see when I turn into his street? Is he smoking a cigarette at his back door? Door ajar always (he’s always too hot), half of his attention on the Grand Prix that was a soundtrack to my childhood during my weekend visits.

Will I see the mongrel dog, Sammy, that my mum had given to him as a companion? A gift to soothe the loneliness that shrouded the house since they'd separated so many years before.

She'd turned up with the dog one Sunday afternoon. I remember it well. Sammy had trembled and pissed all over me in the backseat of the car before we'd even hit the motorway – a bad sign. The dog was unannounced, unasked for. My dad was cool in his response but willing to silently give it a go.

My six-year-old heart broke when Sammy was rehomed five weeks later.

My nana did the deed. She slipped the dog away with his blanket and collar while I was at school. I was distraught. The feeling didn’t settle as the adults had hoped it would. My nana, probably feeling the guilt of having taken Sammy away, told me she'd personally spoken to his new owners, and they'd confirmed he was happy, living on a farm with lots of green space.

He never sat down, my dad.

He always had a bad lower back, constantly aching and painful. He never did anything to get it sorted. I wonder now if that was some form of self-abuse – like the alcohol, he never seemed to really like himself.

I'm too young at this point, in the story, to spot the clues and connect the dots that I so ably do now. I write to understand better those things I didn't back then.

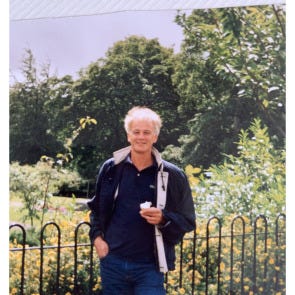

The happiest I will ever see him in his life

This is the happiest I will ever see him in his life. Things get worse from here.

Forty years later, I ask him if he’s happy, and he asks me in return: "What is happiness anyway?"

In this past life memory, he is energetic, curious, motivated, and inspiring in a way that’s stayed with me my whole life. He tells me about the incredible world beyond the red front door of number 53 Lingard Street, a world beneath the sea, ghosts, and life where space stops; he gives the best hugs.

I was five years old when he gave me a tower of 50 pence pieces – the big original ones that weighed a tonne – and in that instant, I was rich with all I’d ever need.

The stash beneath the stairs

The 50-pence pieces come from his stash for the electricity meter under the stairs. A grey, domineering box that ticks away and eats all of his dole money. It sometimes shuts down during the middle of our Saturday night Elvis film-a-thon , plunging us into a sheer blackness that grips my tiny stomach.

He knows it frightens me, that I panic in the dark. While I screw my eyes shut and draw my knees up to my chest, he sings out to me – Roxy Music songs, Elvis songs, silly jokes and impressions — anything to break the silence while he scrapes around for the 50 pence piece that will reignite our Saturday night.

When he does, my childish perception of danger is gone in the drop of the coin in the grey box that keeps him prisoner Monday to Friday. I now understand that he rations the coins across the week to avoid blackouts during my weekend stays.

It’s here that I'll leave him, for now, because he's happy, and things get sad after this point.

This is a touching and beautifully written piece, especially the part where you say, "I come here to try and grasp the ghostly hand of my dad." It feels like you've opened your heart and taken me back to your childhood — reminding me of the warm hugs my dad used to give, they were the best 💜

Oh gosh, Nat. Such a beautifully-written piece - sending love.